|

| Key Lime Pie photo by Marc Averette from Wikimedia Commons |

Legend says a woman named Aunt Sally created the now-famous pie recipe in the late 1800s in what is today the historic Amsterdam-Curry Mansion Inn. Older versions of the story suggest that Sally was a cook who worked for the Curry family that owned the property at the time.

When I first heard the story, I wondered if Aunt Sally was a woman of color. Kitchen jobs in that place and time were almost always filled by women of color. They didn't have many employment options from which to choose. Unless they ran their own business, they were usually pushed into cook, maid, nanny and other domestic jobs.

Also, in the post-Civil War South, mature woman of color were often called Aunt or Auntie. I thought it sad no one knew the full name of the woman who created such an amazing pie. It seemed insulting to just credit it to Aunt Sally.

But we do know Aunt Sally's full name, or at least we think we do. She wasn't an employee. She was a member of the Curry family.

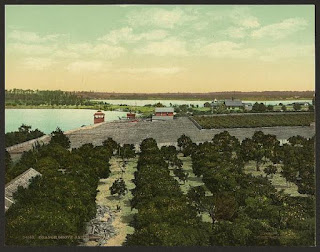

She dreamed up the delicious dessert in the Caroline Street home built in the 1860s by patriarch William Curry. The structure predates the current Amsterdam-Curry Mansion Inn on the same site. The current mansion was built in 1901 by William's son Milton, according to the inn's website.

The online history says Milton demolished everything except the cookhouse in 1901. Today, the only parts of that once-saved structure to remain "are the brick chimney and tiled hearth that once contained the wood-burning stove." One can imagine Aunt Sally standing on that spot and perfecting her pie recipe.

So who was she? The best theory is that she was Sarah Jane Lowe Curry, wife of one of William Curry's other sons, Charles.

A 2019 article in the Keys Weekly by David Sloan dug into the background. David unearthed census records and more in his quest to find a cook named Sally in late 19th and early 20th century Key West. He came up empty.

His father, a genealogist, picked up the trail and found Sarah Jane. She and her husband lived next door to the William Curry/Milton Curry house. Sarah Jane was white and is believed to have been Bahamian. She was affectionately known as Aunt Sally by the numerous Curry nieces and nephews. It was a large extended family.

I lean toward this story rather than the one put forth in 2018 by an author who claimed Key Westians did little but improve a Borden company recipe for a condensed-milk citrus pie. David Sloan is the author of the Key West Key Lime Cookbook. He ought to know.

So there you have it. An unproven but plausible story about the birth of Key Lime Pie. Now you need a recipe to go with it. I have an old -- 30 years? more? - recipe sheet from what was then known as The Curry Mansion Inn. The paper is old enough to contain the early version of the legend. The recipe, however, remains timeless.

INGREDIENTS

4 eggs, separated

1/2 cup key lime juice

14-oz. can sweetened condensed milk

1/3 cup sugar

Graham cracker crust in 8-inch pie pan

Beat egg yolks until light and thick. Blend in lime juice, then milk, stirring until mixture thickens. Pour mixture into pie shell. Beat egg whites with cream of tartar until stiff. Gradually beat in sugar, beating until glossy peaks form. Spread egg whites over surface of pie to edge of crust. Bake at 350 degrees F. until golden brown, about 20 minutes. Chill before serving.

I know, meringue. It's a lot of work. That's the traditional recipe, though. If you don't like that version, there are lots of other ones floating around online. Just be sure to always, always, always make Key Lime Pie with the juice of the small, round, greenish-yellow key limes, never ever with those bright green limes usually seen in supermarkets. If you're going through the trouble to make the pie, you want the real thing.