|

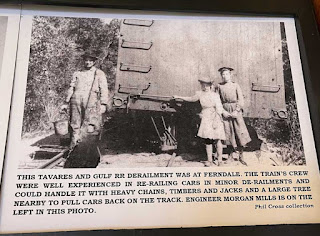

| Partial cover of Rev. Anderson's book. Photo credit: DocSouth |

I tend to consider legitimate self-publishing a fairly recent phenomenon. Something that started when Amazon went up against the publishing gatekeepers. Before that, there were only vanity presses that most writers shied away from.

Ditto for my thoughts about authors marketing their own work. Both traditionally published and indie published writers must do that today. But they also did so in the past.

Writers have been underwriting their own works for a long time. Jane Austen and Charles Dickens come to mind among the biggies. Authors have long promoted their own works, too. I recently found an unknown-to-me, intriguing example: a book published in 1895 by a Georgia minister named Robert Anderson. He undertook months-long trips to market and sell his self-published memoir about his travels throughout the Eastern United States.

He wrote Rev. Robert Anderson's Surpriser when he was 75 years old. It's an autobiographical account of the people and places he encountered on trips through Florida, other Southern states, and Northern states in 1893 and 1894. Everywhere he stopped, he actively promoted and sold his books and also preached when invited. He found selling more difficult in Northern cities than in Southern ones.

For purposes of this blog, I'll share some of Anderson's experiences in Florida. But it's Anderson himself I want to learn more about.

The book's unsigned Preface says Anderson was born in 1819 and is "is among the oldest colored men now living in Georgia." The Preface also states that the book was currently in its 5th edition and providing the author his only means of income. His advanced age hampered his ability to conduct his life's work, the ministry.

Other biographical gems in the Preface point out that Anderson became a citizen in 1838, was employed by banks in Macon, Ga., in his younger days and was known throughout Georgia and other parts of the South.

Anderson himself tells readers, in his book's subtitle, that he "united with the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1839." He seems to have had a lengthy career in ministry as well as the jobs in four banks in Macon.

Anderson also writes of having a guardian after he purchased himself and his wife for $1,500 during the days of slavery. He shares this matter-of-factly as part of an anecdote about an encounter during his travels. Otherwise, the reader learns little of his early life or how he felt about social conditions.

That $1,500 was an incredible sum of money in the 19th century. Did Anderson earn it at the banks? In ministry? Later in the book, he comments that he also bought his mother and grandmother out of bondage. Many questions are unspoken and unanswered. How did he become a good writer in an era when education was denied to most Blacks in the South? Why was he so prominent as an elder? How did he come to have such a widespread reputation?

Early in the book, Anderson thanks the many people who bought previous editions of his book and lists each buyer by name and state. Buyers were generous - many paid the modern equivalent of $30 to $50 per copy.

Buyers were also often white. Anderson rightly said that was because Blacks didn't have as much disposable income. He also stressed that Southern Blacks needed education and a financial step up. But he also expected people, both white and Black, to act respectably and responsibly and to get along peaceably. He is firm in his opinions and his moral stance.

Anderson says he encountered "bitters and sweets" during his 1893 and 1894 travels, but the book overall has a positive tone. Still, there were some tensions. In Boston, Anderson was accused of being on a public relations journey to boost Georgia's image and contradict what Ida B. Wells was writing about lynchings in the South. He denied the charge in the same measured tones he uses throughout the book.

Other receptions were more cordial, particularly in the South. Anderson comes across as a truly Godly man. He stayed with church ministers and congregation members whenever possible and did numerous guest preachings. He traversed color lines and said many people gave him money even when they didn't buy a book.

In Florida, one lady who purchased a book also sold Anderson oranges at a penny apiece. The woman then gave him money for freight charges needed to ship the oranges to his family in Georgia. One minister and his wife refused to accept payment for boarding Anderson for 11 days in Jacksonville.

St. Augustine's sights impressed Anderson, particularly Fort Marion (as Castillo de San Marcos was known at that time), Flagler's Hotel Ponce de Leon, and the city's paved streets. "If you want to see heaven on Earth, come to St. Augustine," he writes. "I never saw such splendor in my life."

The splendor, right now, to me, is that we have Rev. Anderson's travel memoir. I felt I started to get to know him, and I wanted to learn more. I wish there was a biography or that he left a full autobiography.

Read the entire Surpriser text online at Documenting the American South, also known as Doc South. The website's about page explains DocSouth as a digital publishing initiative by the library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The site's collection is amazing. Prepare to spend a lot of time there.