|

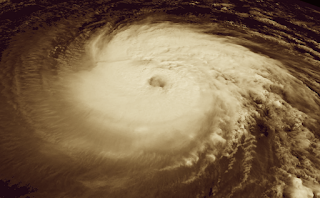

| Memoir tells of the 1928 hurricane |

Well, we're back in another hurricane season. Not something to be taken lightly.

Early settlers had their share of storms and the results could be frightening. Like today, it depended on the severity of the storm and its path. Two pioneer memoirs illustrate that in a vivid way.

The lighter remembrance was viewed through childhood eyes. Maria Davidson Pope wrote Remembrances of an Early Daytona Childhood fairly late in life - in her 60s or older. She was born in Daytona in 1874 and died at age 94 in 1969.

She recounts with great detail the people and times of her youth. That includes periods of bad weather. As a child, she looked "forward to the fall gales with delight." These storms may or may not have been hurricanes. They were fierce enough to rattle windowpanes and blow boats loose from the wharves.

Flooding was a given on the low riverfront land. To lively children in a safe haven, that was an adventure. When the kitchen flooded, they played in the water, she wrote. "I remember paddling around on a small wooden table, turned upside down. Our great delight was to walk on stilts through the water. I so well remember the Puckett boys making me those stilts."

Adults have different perspectives. In Memoirs of an Everglades Pioneer, Gertrude Petersen Winne shared dramatic memories of the horrible 1928 hurricane that tore through South Florida and killed thousands of people.

There's a world of difference between a fall gale and that vicious 1928 storm, known as the Okeechobee Hurricane. An excellent fictional account is in Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. I'd long thought the underprivileged bore the brunt of that storm. Winne's memoir tells me otherwise. Rich and poor alike suffered. One difference is that more well-off residents may have had better access to weather forecasts.

Winne and her family lived near the edge of Lake Okeechobee. Her husband was a fisherman in tune with the ways of wind and water. They heard the storm forecasts and watched conditions closely. "When the water in the creek rose 6 inches in 15 minutes, Ross [her husband] said, 'It's time to go.' "

They grabbed a few belongings and set out for West Palm Beach. They encouraged neighbors to do the same. Most declined. All - or almost all - who stayed behind died. The Winne family's three-story house was washed off its foundation and destroyed.

The family almost didn't make it, themselves. The storm lashed into them before they reached West Palm. The car stalled out. When her husband opened the car door, the wind tore it back and bent the hinges. He shielded himself until a short break in the wind allowed him to get the door back on and get inside the vehicle. He'd also pushed the car into deep sand for stability and put rocks in front of the wheels.

The couple and their children huddled inside the vehicle. They watched pine trees bend to the ground under the wind, saw roofs peel off buildings, and prayed that debris flying all around them wouldn't smash into the car. "During all this, the car surged and swayed like a mad ship but did not break loose from its mire of sand," Gertrude wrote.

During the eye of the storm, they got out and found that the paint on the car's exterior had been scoured off by flying sand. And heavy timbers had been forced into the asphalt pavement only a few feet behind the car. The family got the car started and managed to limp to safety in town, sometimes first getting out of the car and clearing the roadway of debris.

As soon as the storm ended, rescuers including Gertrude's husband headed out to the Everglades, she wrote. "The first truck to return from the Glades came in about 10 o'clock that night loaded with men, women, and children. Ross said if he lived to be a hundred, he would never forget the look on those people's faces - utter hopelessness and despair; some of the people looked so blank and bewildered they had to be led by hand."

Gertrude wasn't able to return home for over a month. Her husband helped nonstop with rescue efforts and with burying the dead. It was gruesome. "Death. Death and destruction lay everywhere," she wrote. "Some 2,000 or 3,000 people lay dead, scattered over the countryside..."

If you live in a hurricane zone and a warning is issued, heed it. Please. We're a century past these pioneer experiences, but some things don't change. The destructive powers of hurricanes are one of them.

To learn more about the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, see the National Weather Service's memorial page at https://www.weather.gov/mfl/okeechobee