|

| My grandmother Rose Russo embroidered this in the early 1900s. |

I wonder where those works of art are today. Handed down in families? Or are they the pieces I see for sale on eBay, Facebook and elsewhere online?

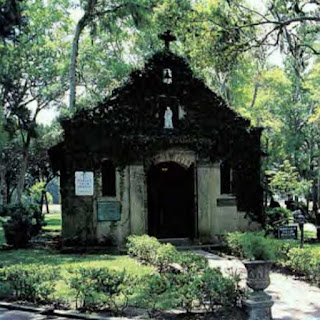

The question arose after I recently took out and refolded the family heirloom linens I inherited. My Sicilian immigrant grandmother created them in New York City between 1910 and 1918. In the same era, a sizeable cluster of Sicilian immigrant women lived and worked in Tampa's Ybor City. Information about their role in the city's cigar-making industries is fairly easy to locate. Information about their domestic lives, not so much.

Yet, as historian and USF professor emeritus Gary Mormino pointed out in a 1983 Florida Historical Quarterly article about Ybor City Italian women, it was family - not work - that was the primary focus of these women. That was true even when they worked outside the home.

Everyone labored to ensure the family survived and thrived. In the early 20th century, Sicilian children routinely were pulled from school and sent to work. My grandmother had only a third-grade education. Her counterparts in Florida had similar experiences.

Mormino's article isn't about needlework. But within it, a sentence tells me how much the traditional and cultural Sicilian skill remained an integral part of immigrant life in Ybor City: "While at home, Italian women somehow found time to continue the handicraft arts of sewing, crocheting, and embroidering."

My Sicilian grandmother worked in a sweatshop, yet turned out beautiful embroidered needlework including the piece pictured with this blog. She was from the same region of Sicily as most of the Sicilian women in Ybor City. Needlework was an important part of their lives. It wasn't a hobby as it is today for me. They were making bed and table linens for their trousseaus. They were preparing for future family life.

So, I have a lot of questions. Did these women in Tampa sit and sew together? Did they bring handworks-in-progress to community outings? Did the needlework provide cultural closeness to all they'd left behind? Where did the designs come from? What stores supplied the fabric and thread? Were the materials mailed to the women by relatives?

Above all, where did all that beautiful cutwork embroidery and other needlework go? I speak of the pieces that were special, not the everyday ones used until threadbare. Some of the fine needlework is artistic and belongs in museums. Is it showcased anywhere?

Traditionally, the finest pieces were handed down. But even that practice is fading. Younger generations aren't as interested in the heirloom linens. Yet each piece has a face, a life, a story behind it. They cry out to be remembered.