|

No matter your heritage, it's easy to agree

that the savory sausage bread Spehovka

is delicious. (Photo credit: Gerri Bauer) |

Everybody is labeled in this era of identity politics. Yet each label holds within it multiple complexities and distinct characteristics.

One of my labels is Slovenian-American. My paternal grandparents and other paternal-side relatives were immigrants from Slovenia, where their roots were centuries deep. They left their homeland when it was still part of Yugoslavia. Tiny Slovenia proclaimed its independence in 1991.

The outside world knew my father's family as Yugoslavian. Within the family, they were always Slovenian. And proud of it. That heritage passed to me.

When I moved to Florida, I was delighted to learn there was a Slovenian community west of New Smyrna Beach. There aren't a lot of Slovenians in the world. I felt an immediate kinship, even though I'd never met anyone in the community.

The settlement began as Briggsville, and later became known as Samsula. It was founded in the early 1900s as a farming community and remains agricultural today. All kinds of vegetables were and are grown there: corn, peppers, squash, onions, cabbage, greens, etc.

Although named after a man from Bohemia named Lloyd Samsula, the community is Slovenian in heritage. Many Slovene immigrants were among the earliest settlers, according to the history shared on the Samsula Woman's Club website. That history says the first to arrive were members of the Kravanja family in 1912.

Many other Slovenian family names are shared on that website and on the Samsula Historical Archive, a community history website. I searched for names from my family tree, including my grandmother's Kralj and great-grandmother's Habian/Habjan, but came up empty. As a newspaper reporter decades ago, I interviewed a Samsula woman who had started a Slovenian museum in her home. Many items on display - such as clothing and crafts - were somewhat familiar to me. But not enough for a full connection.

When my parents moved to Florida many years ago, I was certain my father would find kindred spirits in Samsula. I encouraged my parents to attend an event at the SNPJ Lodge. The Slovene National Benefit Society organization/lodge has long served as Samsula's social hub.

My father's ethnicity is Slovenian. Yet he carries an Italian surname due to the name affixed to an abandoned orphan in my family tree. My father was informed by some people at the SNPJ Lodge event that he wasn't really Slovenian. The hand of friendship wasn't extended. Just the opposite. He never went back to an SNPJ Lodge event. I don't blame him.

|

| Gerri Bauer photo |

My dad's experience soured my enthusiasm for finding heritage kinship in Samsula. But I still bought the Woman's Club cookbook when it was first published. In that pre-internet time, Slovenian recipes in English were almost nonexistent. My family had a Slovenian cookbook, but it was written in Slovenian, a notoriously difficult language for non-natives.

I was dismayed to discover the Samsula cookbook's recipes for potica featured pecans. No, no, no. Potica is a sweet breadlike cake pronounced, roughly, in English as "poh-teet-za." This delicious treat has always been made in my family with walnuts, not pecans. I suspected the Samsula recipes were regional or country variations, and continued paging through the cookbook.

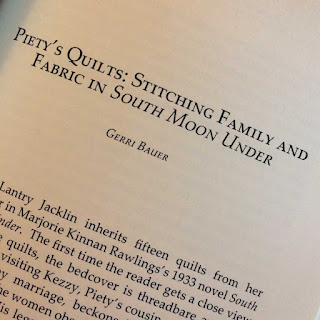

Then, I couldn't find any recipe for spehovka. Later editions of the cookbook may include the detailed steps for this savory sausage bread. To me, it's a Slovenian cultural treasure. My father wrote down his mother's recipe more than a decade ago and became known in the family for his delicious spehovka. I now make spehovka according to family tradition. The first time I made it, Dad happily supervised. I welcomed his advice. It's a challenging recipe.

Yet my family recipe is different than the spehovka recipes I've found in modern English-language Slovenian cookbooks, even some from the motherland. One of these modern recipes even calls for using bacon and eggs as the filling! Not in my spehovka.

Spehovka is one of my culinary specialties, along with Sicilian pizza and lasagna from the other half of my heritage, my maternal side. I'm a mix of cultures, as we all are. Even within our designated labels, we're different, as I learned with my exploration into the Florida Slovenians. We're all human, too, more similar than we sometimes care to believe.

Set aside the labels for a while. Sit down and share a slice of spehovka, or pizza, or sweet potato pie, or flatbread, or beans and rice, or kimchi, or chicken curry ... You get the idea.

As with my blog about everyday life, the novella centers on daily living. My main characters are immigrants who work in one of the hotels that, in reality, were popular in late 19th century Florida. My hotel is fictional, but the long hours of work were real in that time and place. Tourists were wealthy and demanded and received excellence.

As with my blog about everyday life, the novella centers on daily living. My main characters are immigrants who work in one of the hotels that, in reality, were popular in late 19th century Florida. My hotel is fictional, but the long hours of work were real in that time and place. Tourists were wealthy and demanded and received excellence.