|

| Growing a family is a heartwarming romance novel |

Respectability, when it came to motherhood, hinged on marriage. Single and pregnant meant automatic loss of virtue, social standing and chances of a "good" marriage. Forever. Most women in that position faced ruined lives from that moment on.

Options were limited. The term "shotgun marriage" came from, literally, the woman's family threatening the man involved in the pregnancy. The couple sometimes had been courting but were unmarried when they became intimate. The woman's family forced the man to accept responsibility through marriage. Other times, the family paid the guy to marry.

Situations were worse in cases of power imbalances, such as when a servant became pregnant by a man of the household. Even if the relationship had been consensual, it didn't survive public scrutiny. The woman lost her job, her standing and her ability to secure future employment. That held true even if the pregnancy had resulted from rape.

Date rape is how the heroine of my latest novel, Growing A Family in Persimmon Hollow, became pregnant. Date rape wasn't a term that existed in the 19th century world of the novel. But it best describes how the heroine was drugged and taken advantage of. (The scene isn't depicted in the novel - it's referenced as something that already happened.)

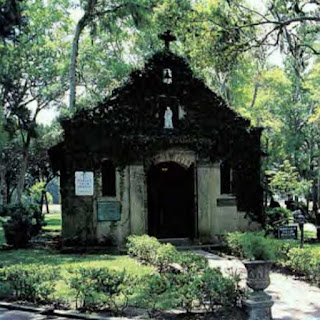

As was typical of the times, her family was scandalized. They sent her away to the frontier Florida town of Persimmon Hollow to hide for the duration of the pregnancy. They also arranged for the baby to be given up for adoption.

Going away and then giving up the baby was a common option, frequently chosen in real life in those days. Sometimes the baby and mother returned home, where the baby was raised by a married sibling or the grandparents. The mother in those cases was relegated to the role of aunt or sister.

In the novel, the heroine - in her shock and confusion - initially goes along with her family's plan. But as she comes to know and love Persimmon Hollow and its people, she undergoes a change of heart. She starts thinking about keeping her baby. And of adopting an oprhan. Things get even more complicated when she grows close to a visiting archaeologist who is unaware of her pregnancy until she physically can't hide it anymore.

The novel is a historical romance, so you know it has a happy ending. The love, faith and community found in the fictional town of Persimmon Hollow surround the heroine and help her find a new path in life. She finds a new family and reconciles with her relatives.

As with current events, real-life history can be harsh in what it reveals. I like to help modern readers understand how life was lived back then. But I also like to offer a warm respite from day-to-day difficulties. A way to relax into another time and place and find joy along the way. I hope you enjoy the book!