|

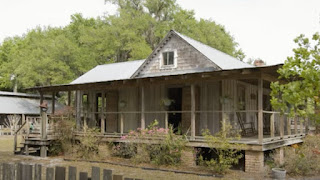

| Market gardening was grueling work in frontier Florida. These19th century homesteaders are harvesting cucumbers. |

Florida frontier life was always challenging. Hurricanes were one obstacle among many. Newcomers learned the hard way. Many had been lured to Florida by promotional material that emphasized and exaggerated the state's potential.

That resulted in some seriously annoyed transplants. "Most of the market gardening in Florida, so far as we know it, cannot but prove disastrous," was the verdict of three Vermont brothers after a few years here in the early 1870s.

They blamed the false promises fed to them before arrival. "Land agents and visionaries hold forth that great crops may be expected from insignificant outlays; and so they decoy the credulous to their ruin."

Those are sharp words. More surprising is that they appear in an 1873 book written specifically for new settlers in post-Civil War Florida.

As usual for that era, the book has a weighty title: The Florida Settler, or Immigrants' Guide, A Complete Manual of Information Concerning the Climate, Soil, Products and Resources of The State. The contents were compiled by D. Eagen, commissioner of Lands and Immigration.

Eagen reached out to Florida locals and asked them to submit reports on their counties. They replied with specifics about climate, crops, terrain, industries, wages, transportation, economic outlooks and occasional descriptions of a town's business district. (Zero mention of domestic details that so interest me.)

As expected, positive aspects are highlighted. Some go beyond that, though. The correspondent from Madison County wrote that "Florida is in need of an energetic, thorough-going, stirring, enterprising, industrious class of men. The late unhappy and unfortunate civic strife seems to have dwarfed our energies, and as of yet we have been unable to shake off our lethargy or gain anything like our former vigor."

The "civic strife" was, of course, the Civil War. It had ended a mere eight years before the book was published.

The Vermont brothers were among early post-war newcomers, as they were already planting in 1870. They bought 275 acres near Mandarin for $275. That's about $5,300 today. They - and/or their hired workers - cleared 35 acres for planting.

Mrs. H.B. Stowe recounted their agricultural experimentation in a Christian Union article reprinted in the 1873 book. I'm guessing Mrs. Stowe was Harriet Beecher Stowe, who owned a home in Mandarin.

Despite the brothers' harsh words, in the end they said their best market crops were "handsomely remunerative." That was after a lot of trial and error. They discovered the need for ample fertilization the hard way. They also learned what crops to plant and when to plant them.

Among the challenges they faced during their first three years:

- Cabbage seeds sowed in sandy soil without manure resulted in weak plants beaten down by rain. Entire crop was lost.

- Three acres of cabbage were half ruined by a Christmas frost.

- Four acres of cucumbers planted in "new, hard, sour land" produced a "wretched crop."

- A hailstorm prematurely spoiled what had been the following year's otherwise good crop of cucumbers.

- Tomato plants were lost to rain, wet land and insufficient fertilizer. A heavy rain also helped ruin the next year's crop.

- A Christmas freeze killed half an acre of blooming pea plants.