|

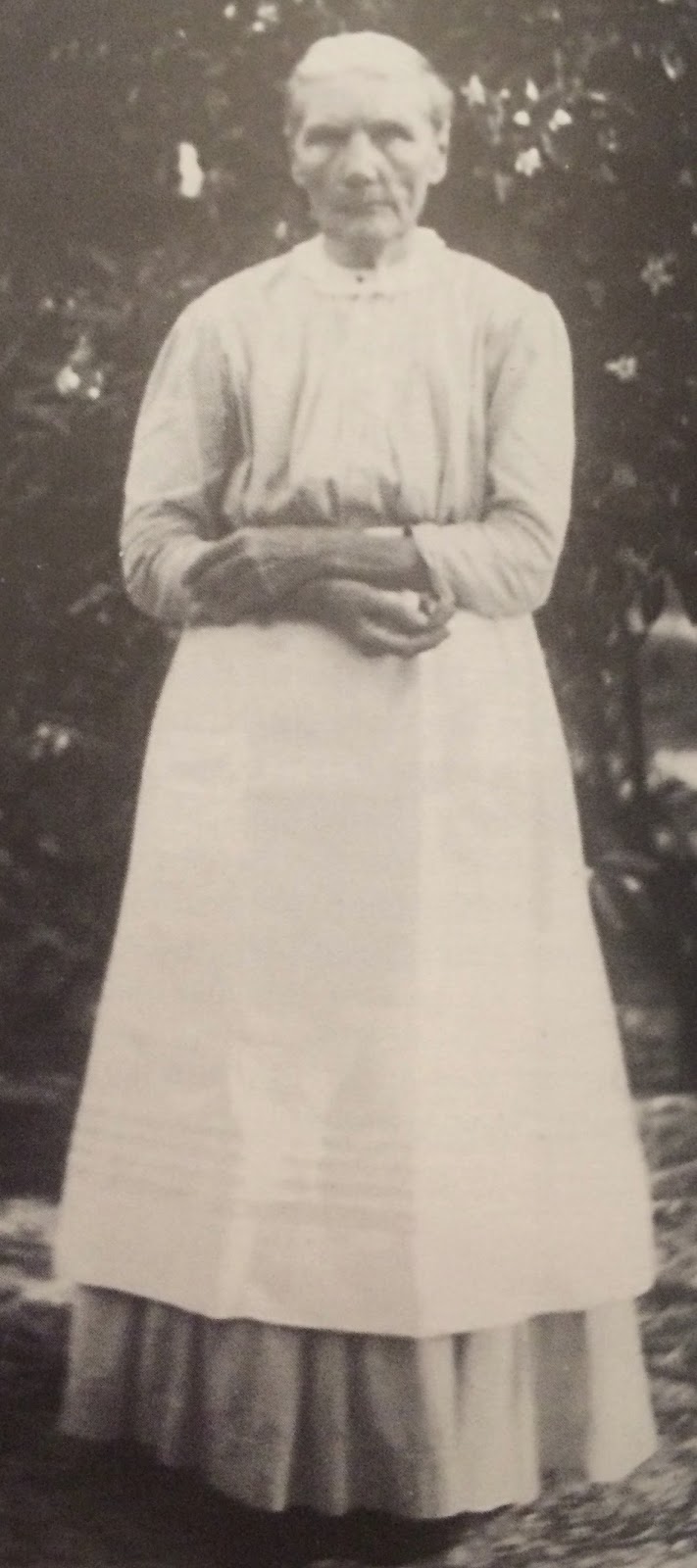

| Ready for dinner on Christmas Day 1885. Is the decor tasteful or showy? It can be hard to tell. (Credit: State Archives of Florida) |

This picture depicts a Christmas dinner at what is labeled on the Florida Memory website as a "restaurant or club" in DeLand. I've seen this photo before, though, and it shows the Putnam Inn.

DeLand in 1885 had some notable boarding houses, and the Putnam Inn was one of the them. Others included the Parce Land Hotel and the Grove House. Another photo on the Florida Memory site shows the same room, set for dinner, but without the wait staff and centerpiece display. It clearly states that the image is of the dining room of the Putnam House (the hotel's later name) on Dec. 25, 1885.

The mystery (to me, anyway) is the condition of the palm-frond decorations. They are decidedly droopier in the image identified as the Putnam and dated Dec. 25.

I share the photograph now - a few days after Christmas - for two reasons:

- The 12 Days of Christmas begin Dec. 25, they don't end on that day. So it's still Christmas, in my book. (When I was a child, we didn't decorate our tree until Dec. 24, a tradition that generated much youthful whining.)

- People who dined out in 1885 Florida had more disposable income than the average pioneer family. The diners were often winter residents, and some were fairly wealthy. Yet there isn't anything really fancy about the dining room. The decorations aren't lavish. The table decor is notable only for the fanned napkins. The scene, overall, leads me to think people back then didn't expect over-the-top everything as many do today.