|

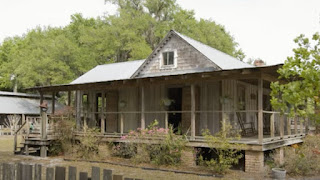

| Easy to make and tasty to eat! This was made from the adapted recipe, using homegrown sweet potatoes. (Gerri Bauer photo) |

(If you're here for the recipe and not the blog post, skip right down to the end of the post!)

Recently, I read that some Hastings, Florida, potato-chip farmers are diversifying into sweet potatoes. The University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences article called the tubers a re-emerging crop. I never realized sweet potatoes had vanished from the state's farms. A weevil caused the industry's demise about 30 years ago.

The crop was a standard item during pioneer years. One old history book talks of a famous "Forty to a Hill" sweet potato venture established commercially in Alachua County in 1891. Specifically, in tiny Waldo, which has a population today of about 1,000.I didn't quite get 40 sweet potatoes out of the one I planted last spring, but it was a healthy harvest. The taters were tender and yummy, and cultivation was minimal. Actually, I was kind of surprised at the result. My husband and I were experimenting when we planted one potato in an old recycling bucket filled with a mix of oak leaves and pine straw. We did little except incorporate organic fertilizer into the soil-less mix when planting, and then water during dry spells.

Ease of cultivation helped make the tasty tuber a nutritional staple for pioneer settlers. In a letter to the Florida Agriculturist newspaper in 1892, one poor newcomer to the state bemoaned that "I am so tender that I even don't know how to grow sweet potatoes." He was ashamed to admit it.

The editors obliged him with cultivation information. But the advice included a suggestion to add tobacco stems to the soil to provide potash. Wonder how that worked out. Elsewhere in the same issue another reader wrote that sweet potatoes cost 70 to 80 cents a bushel that year.

After our big harvest, we let the tubers cure for a couple of weeks and started to feast on them - plain except for butter added to the cooked potatoes. But who can resist sweeter sweet potatoes during the holidays? For Christmas dinner, I made Orange Sweet Potatoes that were a big hit. The preparation is super simple.

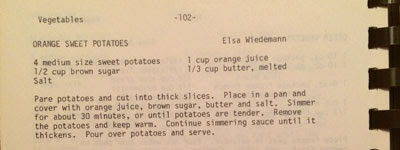

My recipe is adapted from one by a cook named Elsa Wiedemann. Hers is featured in Treasured Recipes, the 1983 cookbook published by the Guild of the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Daytona Beach.

The differences from the original recipe is my addition of maple syrup when reheating, and one change in preparation. If you cook the dish the night before, the sauce thickens on its own in the refrigerator overnight. It stays nice and creamy when reheated. (The original recipe calls for the sauce to be boiled down to a thick consistency on the stovetop after the potatoes are cooked and removed.)

If you think about it, either version could easily have been made by a pioneer Florida cook. Except she or he likely would have used cane syrup as the sweetener.You don't need to wait until a holiday to make this. Enjoy!

ORANGE SWEET POTATOES WITH MAPLE SYRUP

4 medium sweet potatoes

1 cup orange juice

1/2 cup brown sugar

1/3 cup butter

Dash salt

1/3 cup real maple syrup, or more to taste

Pare the sweet potatoes, slice thickly, and place in saucepan. Add all other ingredients except the maple syrup. Bring to a boil and let simmer until potatoes are tender, about 30 minutes. Remove from heat. Cool and store in microwaveable container. Chill overnight in refrigerator. Before reheating, stir in the maple syrup. Reheat and serve.

|

| Here's the original recipe if you'd like to try it, too. |

'